Lesson 9

Inflation

My dear, here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place. And if you wish to go anywhere you must run twice as fast as that.

Trying to understand monetary inflation, and how a non-inflationary system like Bitcoin might change how we do things, was the starting point of my venture into economics. I knew that inflation was the rate at which new money was created, but I didn’t know too much beyond that.

While some economists argue that inflation is a good thing, others argue that “hard” money which can’t be inflated easily — as we had in the days of the gold standard — is essential for a healthy economy. Bitcoin, having a fixed supply of 21 million, agrees with the latter camp.

Usually, the effects of inflation are not immediately obvious. Depending on the inflation rate (as well as other factors) the time between cause and effect can be several years. Not only that, but inflation affects different groups of people more than others. As Henry Hazlitt points out in Economics in One Lesson: “The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.”

One of my personal lightbulb moments was the realization that issuing new currency — printing more money — is a completely different economic activity than all the other economic activities. While real goods and real services produce real value for real people, printing money effectively does the opposite: it takes away value from everyone who holds the currency which is being inflated.

“Mere inflation — that is, the mere issuance of more money, with the consequence of higher wages and prices — may look like the creation of more demand. But in terms of the actual production and exchange of real things it is not.” Henry Hazlitt

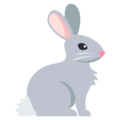

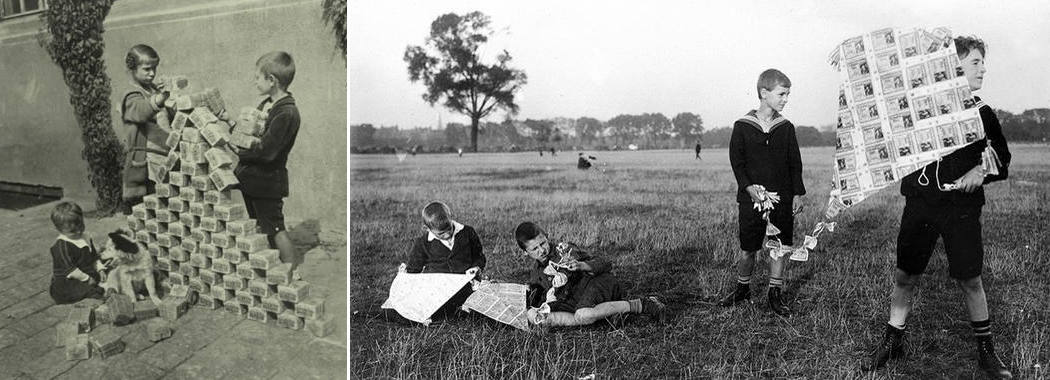

The destructive force of inflation becomes obvious as soon as a little inflation turns into a lot. If money hyperinflates, things get ugly real quick. As the inflating currency falls apart, it will fail to store value over time and people will rush to get their hands on any goods which might do.

Another consequence of hyperinflation is that all the money which people have saved over the course of their life will effectively vanish. The paper money in your wallet will still be there, of course. But it will be exactly that: worthless paper.

Money declines in value with so-called “mild” inflation as well. It just happens slowly enough that most people don’t notice the diminishing of their purchasing power. And once the printing presses are running, currency can be easily inflated, and what used to be mild inflation might turn into a strong cup of inflation by the push of a button. As Friedrich Hayek pointed out in one of his essays, mild inflation usually leads to outright inflation.

"”Mild” steady inflation cannot help — it can lead only to outright inflation.” Friedrich Hayek

Inflation is particularly devious since it favors those who are closer to the printing presses. It takes time for the newly created money to circulate and prices to adjust, so if you are able to get your hands on more money before everyone else’s devaluates you are ahead of the inflationary curve. This is also why inflation can be seen as a hidden tax because in the end governments profit from it while everyone else ends up paying the price.

“I do not think it is an exaggeration to say history is largely a history of inflation, and usually of inflations engineered by governments for the gain of governments.” Friedrich Hayek

So far, all government-controlled currencies have eventually been replaced or have collapsed completely. No matter how small the rate of inflation, “steady” growth is just another way of saying exponential growth. In nature as in economics, all systems which grow exponentially will eventually have to level off or suffer from catastrophic collapse.

“It can’t happen in my country,” is what you’re probably thinking. You don’t think that if you are from Venezuela, which is currently suffering from hyperinflation. With an inflation rate of over 1 million percent, money is basically worthless.

It might not happen in the next couple of years, or to the particular currency used in your country. But a glance at the list of historical currencies shows that it will inevitably happen over a long enough period of time. I remember and used plenty of those listed: the Austrian schilling, the German mark, the Italian lira, the French franc, the Irish pound, the Croatian dinar, etc. My grandma even used the Austro-Hungarian Krone. As time moves on, the currencies currently in use will slowly but surely move to their respective graveyards. They will hyperinflate or be replaced. They will soon be historical currencies. We will make them obsolete.

“History has shown that governments will inevitably succumb to the temptation of inflating the money supply.” Saifedean Ammous

Why is Bitcoin different? In contrast to currencies mandated by the government, monetary goods which are not regulated by governments, but by the laws of physics, tend to survive and even hold their respective value over time. The best example of this so far is gold, which, as the aptly-named Gold-to-Decent-Suit Ratio shows, is holding its value over hundreds and even thousands of years. It might not be perfectly “stable” — a questionable concept in the first place — but the value it holds will at least be in the same order of magnitude.

If a monetary good or currency holds its value well over time and space, it is considered to be hard. If it can’t hold its value, because it easily deteriorates or inflates, it is considered a soft currency. The concept of hardness is essential to understand Bitcoin and is worthy of a more thorough examination. We will return to it in the last economic lesson: sound money.

As more and more countries suffer from hyperinflation, more and more people will have to face the reality of hard and soft money. If we are lucky, maybe even some central bankers will be forced to re-evaluate their monetary policies. Whatever might happen, the insights I have gained thanks to Bitcoin will probably be invaluable, no matter the outcome.

Bitcoin taught me about the hidden tax of inflation and the catastrophe of hyperinflation.

Through the Looking-Glass

Down the Rabbit Hole

- Economic Crisis in Venezuela by Wikipedia Contributors

- Hyperinflation by Wikipedia Contributors

- List of Currencies by Wikipedia Contributors

- List of Historical Currencies by Wikipedia Contributors

- 🎧 Ben Prentice & Heavily Armed Clown on WTF Happened in 1971?

TFTC#157 hosted by Marty Bent - 🎧 Saifedean Ammous & George Gammon on Inflation, Deflation, and The Bitcoin Standard

SSL#23 hosted by Brady Swenson - 📚 1980S Unemployment And The Unions - Essays on the Impotent Price Structure of Britain and Monopoly in the Labour Market by Friedrich von Hayek

- 📚 Economics In One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt

- 📚 Good Money, Part 2 - The Standard by Friedrich von Hayek